Noncompliant Brian is a light bi-weekly newsletter for Architects and Engineers that rounds up new and flavourful things afoot in the building industry that are specific to the Building Code in the Canadian context.

Education: Adaptability and Seismic Implications of the 2024 BCBC

This one hour presentation will cover the implications of the changes in the 2024 BC Building Code related to Adaptability and Seismic considerations. These changes will come into effect in March, 2025.

This presentation is approved for 1 AIBC LU.

Fall Protection - Window Restrictors

Recently I was asked about when window restrictors are required in a dwelling unit of a Part 9 building. The Building Code sets many occupant safety requirements to protect occupants from falls, including from windows. For dwelling units, the restrictions are set in Article 9.8.8.1. for Part 9 buildings in the 2024 British Columbia Building Code.

Within dwelling units, openable windows are required to be protected by a guard or be restricted from opening more than 100 mm in either the horizontal or vertical direction, by a device commonly referred to as a window restrictor, where the bottom edge of the openable portion of the window is less than 900 mm above the finished floor and the drop on the other side is more than 1800 mm, measured from the bottom edge of the openable portion of the window to the adjacent floor or ground.

In most traditional home design, window rough openings are placed at 36 or 42 inches (915 or 1067 mm) above the floor. This design approach allows avoiding a guard or window restrictor, as the bottom edge of the openable portion of the window exceeds the minimum 900 mm above the finished floor.

However, where additional window area is desired in the design with the bottom portion of the openable window located less than 900 mm above the finished floor, a guard or window restrictor can be avoided where the window is placed adjacent to the ground, a patio, or a balcony that is not more than 1800 mm below the opening. In many cases, windows on the lower-level of a house can meet the 1800 mm height limitation. For upper-level windows, balconies can be provided to avoid a window restrictor.

Another approach is to not make the window openable. However, in the case of bedrooms in an unsprinklered Part 9 building, an openable escape window is required to be provided. In this case, the escape window requirement must be met, which does not allow for use of a window restrictor or placement of a guard in front of the window opening. In essence, the escape window requirements dictate that the openable portion of the window must be located more than 900 mm above the finished floor of the bedroom where the exterior height to the adjacent ground, patio, or balcony is more than 1800 mm.

Using Sliding Doors

The Building Code places restrictions on the types of doors that can be used in building. So, when can a sliding door be used, including vertically sliding doors?

To apply the Building Code provisions, one must first know if the proposed sliding door will be an exit door, an egress door, or a convenience door. The Building Code regulates both exit and egress doors. Exit doors are doors that are part of an exit system (doors leading into, doors within, and doors leading out of an exit system) that provide a protected space for occupants to reach safety. Exits typically include enclosed stairs and nearly all exterior doors of a building. Egress doors are located within the floor area (occupied space) of a building and are in the egress path leading to an exit (access to exit), such as a door from a suite into a public corridor.

Detailed exit door requirements are outlined in Subsection 3.4.6., with specific allowances for sliding doors provided in Article 3.4.6.14. of the 2024 British Columbia Building Code. As an exit door, a sliding door is only permitted where the door leads directly to the exterior and the door can also swing on a vertical axis when pressure is applied. These doors are commonly referred to as break-away sliding doors and are typically power operated and used on commercial building entrances for hotels, and retail stores. There are four exceptions to the above, specifically for detention occupancies, impeded egress zones, self-storage suites, and dwelling units.

Within occupied floor areas, the allowances for sliding doors are more relaxed and sliding doors are generally permitted. However, where the sliding door serves an occupant load more than 60, or the door opens onto a corridor or other facility providing access to exit from a suite or a room not within a suite, the door must also swing on a vertical axis when pressure is applied per the above “break-away” requirements.

Doors that are not required to achieve life safety requirements for access to exit and exiting, can be designated as convenience doors and therefore are not restricted by the Building Code. This is often seen in the case of vertically sliding overhead doors in storage garages and commercial warehousing to allow vehicles, equipment, and materials to be easily moved around and in and out of the building. In this case, occupant egress or exiting requirements are met by pairing the sliding door with a regular swing door so that compliance with travel distance and occupant load requirements are met.

Sliding doors used in an accessible path of travel have additional requirements including door operating hardware that is capable of being opened with a closed fist, and requiring no grasping, pinching, or twisting motions as noted in Article 3.8.3.8. In some cases – the operating hardware may prevent the sliding door from opening to its full width, so care must be taken to ensure that the clear opening will still meet the minimum 850 mm required by Sentence 3.8.3.6.(2). Additionally, sliding doors in an accessible path require a clear floor space with a dimension not less than 1200 mm parallel to the closed door and 1500 mm perpendicular to the closed door. Where a power door operator is used, the parallel dimension is permitted to be reduced to 1000 mm.

Revisions to the 2024 British Columbia Building Code, Division B - Part 3

In cooperation with Nick Bray Architecture, we’re excited to be presenting a webinar focused on reviewing and explaining the changes that you should be aware of when designing to the 2024 BC Building Code.

WHEN: Tuesday, April 16, 12:00-1:00pm

WHERE: Online

COST: Free

AIBC Registered Education Provider: 1 Core Learning Unit

Presented by Marc Showers, P.Eng., C.P., and Brian Fraser, P.Eng., C.P.

Suburban and Rural Water Supplies

The Building Code requires Part 3 buildings to be provided with an “adequate water supply for firefighting”. This provision is intended to ensure that firefighting operations will be effective as part of the OS1 Fire Safety objective with the functional requirement of F02 to limit the severity of and effects of fire or explosion. Where the building is sprinklered throughout, this requirement is deemed met. However, how is this requirement met for unsprinklered building and in rural environments with limited or no municipal water supply available?

In urban environment, the local municipality typically will have planned and installed sufficient water supply for the building uses and sizes in relation to their property use bylaws (often called zoning bylaws) as part of the original subdivision development of the land. However, where the permitted property use allowances are changed as part of a development application, the available water supply can be insufficient to meet the current municipal civil engineering standards and the underlying Building Code assumptions.

In contrast, in rural environment, land may be being developed for buildings for the first time, and an adequate municipal water infrastructure does not exist or at best be severely inadequate.

We often deal with this issue, particularly for rural environments. The Building Code provides some guidance in the Notes to Part 3, and municipalities typically will have a minimum civil engineering standard or mandate the use of the Fire Underwriter’s Survey (FUS) to determine minimum firefighting water supply to the subject site. For urban environments where the dense building environment has a risk of conflagration, the FUS standard is often used and results in a significant water supply demand to support firefighting operations. However, the application of FUS to the rural environment can result in significant municipal upgrades being required that do not make the development feasible despite there being no urban conflagration risk. For the rural environment, alternative water supply design methods such as NFPA 1142, Standard on Water Supplies for Suburban and Rural Firefighting, often provides more affordable options with lower water demand requirement matched to the specific hazard with non-municipal water sources. Water sources can include rivers, ponds, and water storage tanks that are available for firefighters to draft from.

Recently, we supported an aerosol filling plant that was proposed to be located in the middle of a large field in a rural location. The local municipality did not provide a water service infrastructure, with private wells being the only available water source for landowners. For this project, we reviewed the proposed building in accordance with NFPA 1142 and were successful in negotiating with the local authority to provide a service road to the small river that flowed adjacent to the rear property line, so that the fire department could use the river as a water source for firefighting operations in a fire emergency.

If your project has water supply challenges, contact us to see how we might be able to support your project.

Visibility of Exit Signs – Good Practices for Life Safety

The National Building Code of Canada, and subsequently the British Columbia Building Code, (Building Code) generally require buildings to be provided with illuminated exit signs. While these codes provide considerable details about the pictograms associated with exit signs and how they are to be illuminated there is little discussion about visibility of exit signs other than being “visible upon approach to the exit”. Like many of the Acceptable Solutions in Division B of the Building Code this statement is not based on any technical merit as is wholly subjective. This can potentially create life safety issues during emergency evacuations.

CSA 22.2 No. 141 “Emergency Lighting Equipment” requires internally illuminated signs to be placed at intervals so that the maximum viewing distance is no more than 30.5 m, however this is not strictly a requirement in the Building Code. Further, no additional consideration is given to the overall size of the sign. Considering that the legibility of a sign is directly proportional to the size of the sign and the viewing distance, adjustments in sign size should be made based on the viewing distance.

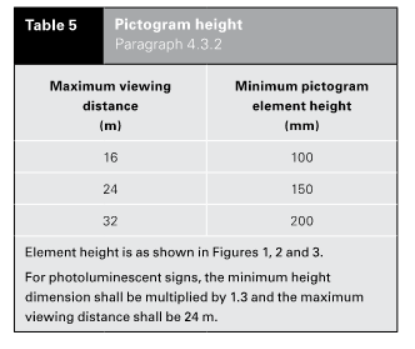

Most international standards provide some guidance on the size of an exit sign with respect to the distance it is viewed at. For example, in New Zealand the compliance document F8/AS1 provides information about minimum viewing distances for both internally illuminated and externally illuminated/photoluminescent signs and exit sign pictogram height.

Acceptable Solutions and Verification Methods for New Zealand Building Code Clause F8

Further, viewing distances greater than 32 m, the minimum element height shall be determined in accordance with the following equation:

Minimum element height, mm = Maximum viewing distance, mm / 160

and rounded up to the nearest 50 mm.

In the United Kingdom, BS 5266 pt7 details exit sign heights as follows:

Internally Illuminated:

Maximum Viewing Distance, mm = 200 X panel height, mm

Externally Illuminated:

Maximum Viewing Distance, mm = 100 X panel height, mm

Although the Building Code does not specifically call out exit sign size, consideration should be given to the size of the sign and the respective viewing distance. This can aid in emergency wayfinding and promote for efficient evacuation.

Tiny Homes and the Building Code

There are many reasons that the buzz around tiny homes is on the rise. It could be the desire to downsize, a way to reduce cost of living, or to minimize your environmental footprint. But do our Building Codes really facilitate tiny home design? Here are a few requirements to keep in mind:

Minimum areas. Gone are the days where the building code dictated minimum room dimensions and areas (the 1990 National Building Code required living rooms to have a minimum area of 13.5m2, with no dimension less than 3m). But that does not mean there are not still local bylaws and community design guidelines that require minimum home sizes, or limit if/where accessory dwelling units can be built.

Minimum ceiling heights. While minimum room sizes may no longer be required by code – minimum ceiling heights still are. Many tiny home designs include lowered ceilings or loft bedrooms, but to meet code - 2.1m (approx. 6’-11”) ceiling heights are required over at least a minimum area for all habitable spaces.

Minimum door sizes. Similar to above, some tiny home plans may not allow for the minimum door sizes of our Canadian building codes. All doors require a minimum 1.98m height, and most interior doors require a 760mm width, though some spaces can be reduced to 610mm wide. At least one entrance door to the dwelling unit must be 810mm wide.

Stairs. This is a big one. Many tiny home designs – especially those that include lofts – provide stairs (or even ladders) that would not meet current code requirements. Stairs within a dwelling unit must be at least 860mm wide. Each step must have a minimum length of 255mm and a maximum height of 200mm. Guardrails are required wherever there is more than 600mm in elevation difference.

As markets and demands change, so may the building code. Just like secondary suites have been added to our codes and include specific requirements (and some relaxations) – we may see more allowances for smaller dwellings. Until that comes – and acknowledging that codes can be notoriously slow to update - be sure to do your research. And as always – we are happy to help!

Accessibility: Updates to the 2024 BCBC and Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification™ (RHFAC)

March 8, 2024, the effective date for the British Columbia Building Code (BCBC) 2024, is quickly moving closer! As a result, we find ourselves digging deeper into this new edition to support our clients and their projects. At the forefront of the changes within Part 3 of the BCBC 2024 is Section 3.8 - Accessibility. This no surprise as we notice accessibility and inclusion driving the path forward in many sectors.

Requirements within Section 3.8 aim to support the disability community, including people with mobility disabilities, vision or hearing disabilities, and people with care providers.

Some significant changes to the BCBC include:

Increased clear area to exterior entrances and pathways,

Modification to required clear space for interior paths of travel which will provide designers with flexibility,

Inclusion of colour contrast to highlight building features, and

Requirements to support wayfinding.

Acknowledging the Building Code provides minimum requirements, good design often goes beyond these minimums to support meaningful access.

An example of going beyond these minimums was demonstrated by the City of Vancouver with their commitment to achieve Rick Hansen Foundation Accessible CertificationTM (RHFAC) Gold for all newly built municipal facilities.

The Rick Hansen Foundation (RHF) is part of the movement to help create a fully accessible and inclusive Canada with the goal to provide meaningful access for everyone. They have developed the RHFAC Rating Survey, a national rating system that provides clients with a snapshot of the overall level of meaningful access of their site.

At Celerity Engineering, Corie Lubben is a RHFAC Professional and can rate pre-construction and existing sites to help clients become leaders in equity, diversity and inclusion, by building accessible spaces that benefit everyone.

RHFAC recently released a new version of their rating survey, RHFAC Rating Survey v4.0, which came into effect January 15, 2024. This new version builds on the previous version and has been expanded to include a wider disability community. An important addition is a new category for Mind-Friendly Environments, which includes new criteria to evaluate how sites accommodate people with various neurological experiences. A second new category, Technology and Innovation, has been added to encourage and recognize innovation and the use of technology to positively impact meaningful access at a site. Updated standards such as CSA B651:23 Accessible design for the built environment and CSA/ASC B652:23 Accessible dwellings are also incorporated within this latest version.

The Rick Hansen Foundation are leaders in accessibility and support inclusion and universal design, and RFHAC v4.0 contains valuable and exciting information which will help accelerate accessible design. Even if your project goal isn’t ultimately to achieve a RHFAC rating, Celerity Engineering can provide comments alongside a typical building code review to help identify barriers and improve accessibility to your site. We look forward to helping our clients integrate these points and practices into their design.

Do Temporary Tent Structures Require a Building Permit in BC?

Yes! Except…. when they don’t.

Because temporary tents do have building code requirements, your municipality (also known as the Authority Having Jurisdiction) may require you to have a building permit. However, they may also waive this requirement, as explained below.

The best choice is to call the authority having jurisdiction right away to determine if they will require your temporary tent structure to have a building permit.

Please note that tents intended for permanent use or occupancy, such as outdoor vehicle shelters, storage, or restaurant patios, must conform to the applicable requirements from either Part 3 or 9 of the BC Building Code (i.e. permanent tent structures used as carports must conform to the Building Code’s Part 3 or 9 requirements for storage garages), and almost always need a building permit.

Why do temporary tents need a building permit?

Tent structures, as understood in the BC Building Code, are temporary structures which have Part 3 requirements that must be reviewed by an authority having jurisdiction.

While not a defined term in Division A, Section 1.4 of the Building Code, the Notes to Part 3 explains that:

“….the word “tent” as used in the Code is intended to refer to a temporary shelter which is used at an open air event such as a fair or an exhibition. A tent will normally be constructed of a fabric held up by poles and attached to the ground by ties.” (A-3.1.6)

The requirements for tent structures can be found in Subsection 3.1.6 of Division B of the BC Building Code and pertain to exiting and egress, occupancy and use, spatial separation, clearance from flammable material, tent material flame resistance, and location of electrical systems. These requirements are reviewed by an authority having jurisdiction and granted approval in the form of a building permit.

Why might the requirement be waived?

Given that tent structures are temporary buildings, the authority having jurisdiction may waive the need for a building permit on the basis of Clause 1.1.1.1.(2)(f) which states the Building Code need not apply to:

“….with the permission of the authority having jurisdiction, temporary buildings including i) construction site offices, ii) seasonal storage buildings, iii) special events facilities, iv) emergency facilities, and v) similar structures.”

As such, you are best to consult with your local authority having jurisdiction to determine if your tent structure will require a building permit.

Give us a call if you need help!

2024 British Columbia Building Code Adoption and Notable Changes

On March 8, 2024, the latest edition of the British Columbia Building Code will officially come into force, except for adaptable dwellings and earthquake changes which take effect March 10, 2025. This phased start allows market sectors that are affected to pivot, adjust processes and acquire the appropriate technology to implement the various changes in the new edition of the BC Building Code.

Based on Canada’s regulatory system this latest installment of the BC Building Code falls in general alignment with the National Building Code of Canada (NBCC) 2020, except for specific conditions that reflect the province’s geography, climate, local government needs, industry practices, and provincial priorities. This is the same approach as previous editions of the BC Building Code (a historic summary of BC codes adoption can be found here).

Over 280 technical changes have been incorporated into the NBCC 2020, improving the level of safety, health, accessibility, fire and structural protection, and energy efficiency provided by the Code, and expanding the NBC into new areas. Notable changes that will be reflected in the revised BCBC include:

Technical requirements for large farm buildings are added, which address fire protection, occupant safety, structural design, and heating, ventilating and air-conditioning.

Encapsulated mass timber construction is introduced, enabling the construction of wood buildings with up to 12 storeys.

Accessibility requirements are updated to reduce barriers related to anthropometrics, plumbing facilities, signage, entrances and elevators.

Design requirements for evaporative equipment are revised to minimize the growth and transmission of Legionella and other bacteria.

A home-type care occupancy is introduced to allow safe and affordable care in a home-type setting.

Energy performance tiers are established to provide a framework for achieving higher levels of energy efficiency in housing and small buildings.

Changes to curtain wall fire stopping to permit testing in accordance with ASTM E2307, “Standard Test Method for Determining Fire Resistance of Perimeter Fire Barriers Using Intermediate-Scale, Multi-storey Test Apparatus”.

Notable changes in the BC Building Code include:

More complete and specific language for constructing extended rough-ins for radon subfloor depressurization systems

Adopting cooling requirements to provide one living space that does not exceed 26 degrees Celsius

Retaining existing ventilation requirements for systems serving single dwelling units

New methodologies for earthquake design for small buildings, in harmonization with the National Building Code.

An elevator in all large two- and three-storey apartment buildings.

Predicting Fire Exposure Hazards

Abstract

This paper details of the development of a framework and assessment tool that can be utilised:

In lieu of the prescriptive requirements detailed in building codes that require fire resistive barriers to separate exit routes from the radiative effects of fire and/or

To address egress past a burning object in an open floor area.

Contained within this paper is a methodology that can aid the user in:

Determining the level of radiation from a fire source imposed on an egress route that is adjacent to the source, and

Determining if the level of radiation will result in sufficient pain to prevent the use of the egress route.

Generally, the calculations are based around quantified fire engineering formulae and good engineering practice.

Cladding in Combustible and Non-Combustible Construction

Introduction:

This bulletin provides some background on cladding systems and clarifies the intent of the code insofar as systems that are tested for use in non-combustible construction and possibly used in the context of combustible construction – such as conventional wood frame.

The intent of the National Building Code is to limit the use and contribution of combustible cladding systems in non-combustible construction. There are a number of mechanisms to achieve this. Use of the same materials in combustible construction is permitted and applications will be clarified in this Bulletin.

Use of Non-Combustible Cladding

Use of materials that are classified as non-combustible- such as pre-formed steel panels and many reinforced cement-based tiles- do not contribute significant fuel to a fire if supported by non-combustible construction. With current energy performance requirements foamed plastic or other insulation may be introduced to reduce heat losses through the wall assembly. This will invoke other code requirements

The contribution of foamed plastics that may be used to insulate wall assemblies is less significant in the context of combustible construction whereas in non-combustible construction, the contribution of fuel can have a significant impact on the expected performance of walls, ceilings/attic spaces and roofs. Consequently, the code requirements are more onerous in the context of non-combustible construction.

Where thermal protection is required for foamed plastic in wood frame exterior wall assemblies this bulletin will clarify the intent of the code for cladding systems.

Composite Materials

Where a composite material is utilised for cladding purposes, the combustibility can increase due to the contribution of insultation in a ‘sandwich-panel’ construction; in this case each element has to be assessed for combustibility. Even where mineral insulation is used in sandwich -type construction it is hard for these composites to meet the code criteria under 3.1.5.1. In most instances the referenced tests will marginally exceed the criteria to be considered non-combustible which means that technically, the cladding material has to be treated as a combustible material- under 3.1.5.5 of the Code.

It should be noted that fire retardant treated wood has a significantly higher heat release rate- 40-50 MJ/m2- than the criteria set out in 3.1.5.1 and significantly higher than most mineral insulated composite aluminum panels (typically around 10MJ/.m2 if non-combustible core). Also, the flame spread of many S-134 tested panels is zero in comparison with FRTW which has a flame spread of 25.

Use of Combustible Cladding in Non-Combustible Construction

Owing to the vertical configuration of cladding systems, higher than expected vertical flame spread can occur than would be expected if the same material were installed in the horizontal position. External Insulation finish system (known as EIFS) is a lightweight synthetic wall cladding that includes foam plastic insulation and thin synthetic coatings. The cladding requirements of the code therefore reflect criteria originally developed for testing of EIFS systems- now set out in the CAN/ULC S-134 test. Although the test criteria for this and other tests such as the NFPA 285 test differ significantly, these tests are intended to be indicative of large scale fire behaviour- and are not that easy to pass without some input from a fire testing specialist. The NFPA test is considered easier to pass than the S-134 test in Canada. Significantly different results can emerge due to the location of the test facility and the weather on the day of the test. The cost of the CAM/ULC S-134 test is somewhat prohibitive and a failure the first time around can quickly escalate costs out of control.

Figure 1: NFPA 285 test in progress.

Figure 2: Images from a recent CAN/ULC S-134 test of architectural cladding system.

Combustible Cladding Options Under the Code

3.1.5.5 of the Code is not entirely clear and a rational explanation of how it should be applied is difficult once different sections and their intent are applied in the context of spatial separation as well as other issues including thermal protection of foamed plastics. That said this bulletin summarises what applies in the vast majority of cases.

Under 3.1.5.5. (1) the use of combustible cladding on unsprinklered non-combustible buildings is limited to 3 storeys- the typical walk up apartment building for instance. Where sprinklered, the use is restricted to:

Assemblies where any foamed plastics are protected by a thermal barrier- on the inside of the building.

Wall assemblies that pass the criteria of 3.1.5.5 (3) and (4) when tested in conformance with the CAN/ULC S-134 “Fire Test of Exterior Wall Assemblies. These sentences are essentially the pass criteria of the S-134 test. It should be noted that the S-134 test does not test assemblies in combustible construction such as wood frame. What this means is that where combustible construction is permissible, it is acceptable to use an S-134 system on the outside of the assembly as it does not significantly reduce the cladding performance if the S-134 pass criteria have been satisfied. The system has to include the complete assembly including the 5/8inch exterior GWB.

Based on sentence 3.1.5.5.(1), fire retardant treated wood would not satisfy the pass criteria of sentence (3) and (4) as heat release of FRTW is too high. Sentence (5) however, essentially permits it despite the restriction under the above pass criteria. Also, 3.2.2.50 of the BC Building Code 2012 for 5 and 6 storey sprinklered buildings, permits both FRTW or an assembly that satisfies the CAN/ULC S-134 criteria and has a thermal barrier on the inside.

Based on the code wording FRTW would be permitted without a thermal barrier unless the assembly incorporates foamed plastic requiring thermal protection.

An assembly tested to the CAN/ULC S-134 would require both a thermal barrier on the inside as well as the external GWB typically incorporated as part of the test assembly. This would be standard practice in wood frame applications where there is often foamed plastic in the wall cavity. However, if used in non-combustible applications without foamed plastic insulation then this would seem to be unjustified.

Going back to the requirements pertaining to combustible cladding in non-combustible construction there is an exception under 3.1.5.5.(2): where table 3.2.3.7 requires non-combustible cladding.

However, there are various exceptions to the requirement for non-combustible cladding and the main restriction is where the permissible openings are less than 10%. In this case cladding must be non-combustible. As such an S-134 tested system would not be acceptable. This is clarified in the Appendix A of Division B Part 3.

Where the openings permitted are at least 10% then 3.2.3.7 (3) defers back to the S-134 pass criteria set out in 3.2.5.5 which we just reviewed.

Where openings are more than 25% and less than 50% FRTW can be used under certain conditions provided the limiting distance is at least 5m and cladding meets the Part 9 requirements. Also, there is also a general cross reference in 3.2.3.7.(5) back to 3.1.5.5 provided the permissible openings are more than 10% and not more than 25%.

Given the ways these sections are laid out it is not surprising that there is confusion over how different requirements are intended to apply.

Foamed Plastic in the Exterior Building Face

There is a series of requirements under 3.2.3.8 setting out criteria for protection of foamed plastic in the exposing building face; however, assemblies that comply with 3.1.5.5 (S-134 etc. again) do not require to meet the requirements set out in 3.2.3.8 sentences (1) and (2). This is confusing as we have seen that a thermal barrier is specified in the requirements for 6 storey wood frame construction. It appears that the 3.2.2.50 requirements anticipated foamed plastic use and therefore have required it under 3.2.3.8 sentence (3). This also applies under 3.1.5.5 (1) (b)

It should however also be noted that fire blocks are required in exterior walls as per 3.1.11- Fire Blocks in Concealed Spaces. Essentially, this requires fire blocking at each storey and every 20m horizontally unless the insulation is either non-combustible or has a flame spread not more than 25 and has vertical firestopping every 10m vertically. Where there is an air space there should be only one air space and the maximum depth of this should be 25mm (1in.)

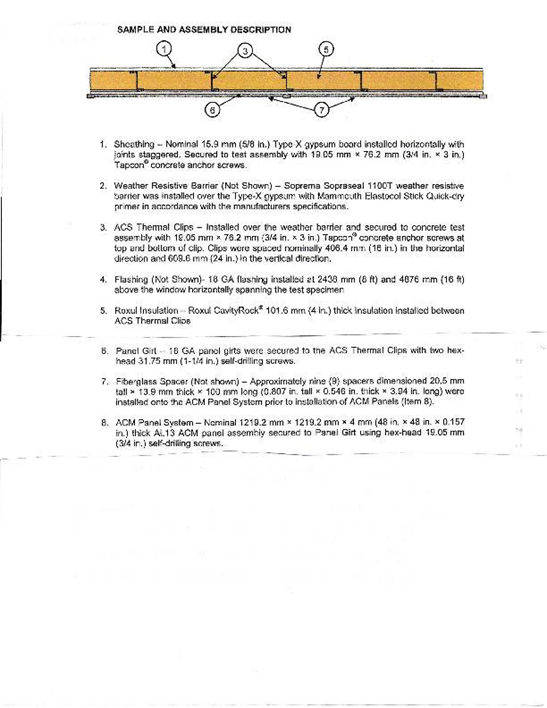

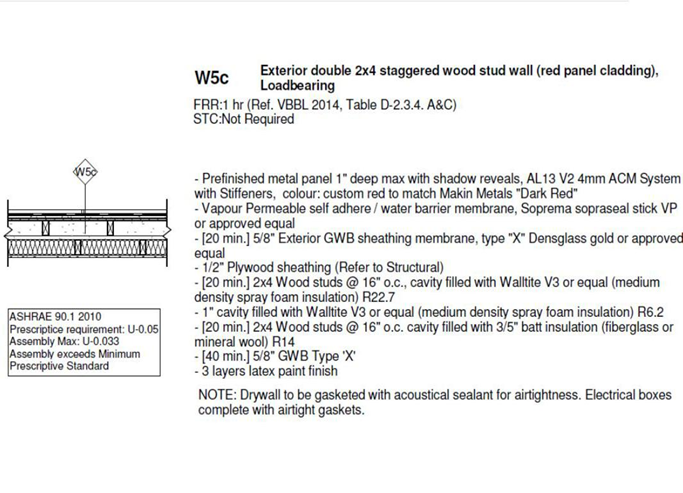

Composite Panel Systems

There are several manufacturers that have successfully subjected their systems to the CAN/ULC S-134 test. These systems are designed for use in non-combustible construction but can be used in combustible construction and will not adversely affect the performance of the wall assembly-even if wood frame. The assembly for non-combustible construction consists of:

If the wall is of combustible construction then it is common to use double- walled construction with insulated cavity walls for energy conservation. Where the wall requires a rating, this is typically provided by 1 or more layers of gypsum wallboard on the room side.

Where foamed plastic is sprayed in place for insulation and thermal performance of the wall the foamed plastic in combustible construction typically requires a thermal barrier with certain exceptions.

In non-combustible construction the exterior requirements are more complex but generally:

In most circumstances except for unsprinklered buildings over 18m a thermal barrier of 12.7 (0.5 in.) is required.

Adjacent spaces in wall assemblies are exempted.

For unsprinklered buildings over 18m the board has to be taped and filled- partly due to potential smoke spread.

Attics, interior walls and ceiling assemblies in unsprinklered buildings over 18m have thermal protection increased to 15.9mm thermal barriers taped and filled.

Factory- assembled wall units are dealt with separately.

Examples of a Composite Panel/Architectural Cladding System.

Generally composite panel system consists of the following components. The following are based on the AL13 architectural cladding system.

In combustible construction, the assembly is typically used on the outside of a double wood frame typically) assembly as shown below.

Summary:

Materials that meet the requirements of 3.1.5.1 are permissible for use in non-combustible construction.

Composite panels utilising non-combustible insulation are not able to be classified as non-combustible per se and are dealt with in 3.1.5.5 and elsewhere in the Code.

Use of systems classified as combustible for non-combustible construction typically are required to:

Have a thermal barrier: generally, 12.7mm GWB.

Satisfy the CAN/ULC S-134 test criteria unless openings are limited to a maximum of 10% or

Satisfy the requirements of FRTW with the same limitation on openings.

Use of CAN/ULC S134 assemblies in non-combustible construction must be the same as the tested assembly.

Use of the same assembly is permitted in non-combustible construction and these should be the same assembly on the building exterior with a thermal barrier on the inside.

Fire blocking has to be provided as destribed herein.

Prepared By:

John Ivison

Date: July 19th 2018

Rehabilitation of Existing Buildings – Listed Historic and Other Structures

Date : February 3, 2016

Subject: Rehabilitation of Existing Buildings – Listed Historic and Other Structures.

Issue Number: 2016-01

Introduction

While new condominiums represent the largest segment of property entering the market, refurbished buildings are in high demand due to their aesthetic appeal. The lack of availability makes these properties attractive to developers as potential rentals and condominium conversions.

The property market dictates the price of accommodation; however, there are many factors affecting the cost of renovations and the ease to which buildings can be modified and upgraded to a reasonable standard. If these costs can be reduced then it increases the bottom line for developers. This cost reduction increases the potential supply of units in the market place. This helps bring supply and demand back into balance.

In the City of Vancouver the aim is to align the scheme for upgrading buildings with Part 11 of the Vancouver Building Bylaw. This Part is now relatively comprehensive and has improved significantly since the 1980’s. Although this bulletin focusses on the Vancouver Building Bylaw it should help inform the approach to be used in other centres. In general, two strategies may be used to define the scope of an upgrading project in cases where the building and/or proposed changes do not qualify for an exception to the upgrading requirements:

Option 1: Identify the scope of upgrading using Vancouver Building Bylaw Part 11 and Division B Appendix A-11.2.1.2. This requires you to select the appropriate chart for the categories of work and extent of upgrading. Many practioners use these requirements and it does not take a significant level of technical expertise to apply the rules.

Option 2. Carry out a fire risk analysis and building code assessment to develop a bespoke strategy for the building improvements. This includes obtaining concurrence of the City / authority on the proposed programme and the intent of the Part 11 / Appendix A requirements for the specific project.

Figure 1: The Leckie Building in Gastown, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Figure 1a: Fire escape on the Dominion Building – Hastings and Cambie, Vancouver, BC, Canada

USING OPTION 1

While Option1 may seem the most practical there are several reasons why this is often not the optimum approach:

The one constant is the endless variety of heritage projects, specific non-conforming features and issues that have to be addressed. If these issues are not dealt with, they will emerge as unanticipated problems and costs in the construction/inspection phases. This is expensive; consequently, all details have to be tied down.

The current bylaw represents the ‘best practice’ based on experience on heritage buildings to date but it has to be constantly updated to reflect new conditions as they are encountered on different projects. The incremental changes are usually made at each code cycle.

Conservation should be the driving force of any heritage project. Often the fabric of the building necessitates a different approach to issues such as fire resistance and combustibility of construction. Key features- for instance, exposed heavy timber or large dimension joists- should be retained wherever possible as they reflect the original character of the period.

If the City staff are asked for advice independently they may take the ‘worst case’ approach and this can significantly increase the project scope and costs.

Ultimately there has to be a process with which the project is aligned. These fall into planning or building permit realms. While building permit processes may be relatively well-defined, in practice numerous issues can delay or complicate a project. Planning is more subjective and the process may become as much political as it is technical.

Figure 2: Larger dimension joists are typical of low-rise Yaletown and Gastown Buildings. These were retained based on improved sprinkler performance requirements.

Planning in Perspective

When a heritage building forms part of a larger development site- combined with new structures- the heritage building may be treated differently to a single heritage building on a site. In the past, the authority has been sufficiently flexible to permit the heritage component of a larger project to be upgraded to a ‘reasonable’ standard rather than to be fully upgraded to Code. Any legal agreements that dictate that upgrading levels must be to current codes should be interpreted reasonably i.e. in the appropriate context for the heritage building. There is no point in requiring full upgrading of any heritage building to current codes. It is counter-intuitive and inconsistent with heritage conservation principles. It is also significantly more expensive and perpetuates the myth that renovation of a building costs more than new construction.

Similarly the conversion of an existing building to condominium use should have reasonable caveats applied. The price for meeting full code requirements can be virtual reconstruction of a building. Any requirement that is imposed to this effect is counterproductive; numerous studies have shown that upgrading an existing building- rather than demolishing it and building new- is both less costly and has a lower carbon footprint than new construction. Therefore any scheme which requires removal of floors and other essential building fabric cannot be easily affordable or considered sustainable.

Many developers rely on architects to come up with a scheme to adapt a building for a new use. While this is an effective strategy, certain architects excel at renovation; others may be less sensitive to retention of the features of a building. Developers that focus on renovation as a principal part of their portfolio have to assemble the best tools at hand to make the project successful. Certain principles have emerged on how to do this.

The heritage features and circulation should be retained or re-used if possible in the new design. Fabric that is proposed to be removed should only be removed if absolutely necessary based on the benefits and costs.

FIG 3: Gastown, Vancouver, BC

Most heritage buildings have existing stairs and any scheme to create new stairs can be invasive. Early reinforced concrete construction does not lend itself to the penetration of floors to create new scissor stairs for instance. The more invasive a scheme is, the bigger the impact on structural upgrading required. Using existing stairs is a more effective way to approach the exiting scheme.Exposed wood floor and roof structures are often a key feature of heritage buildings in Gastown, Yaletown, Victoria and other historic centres.

The material is often clear fir or other old growth timber. Strategies can usually be developed that enable such structure to be cleaned and restored to their original patina/visual condition. Upgrading by encapsulation using gypsum board is counter-productive, invasive and is not recommended for sustainability and other reasons

Figure 3: The preservation of buildings in Gastown has created a successful neighbourhood / tourist destination

Note: For large facilities such as heritage town sites, conservation is the prime driver and often the strategy is site-wide to enable infrastructure to be established and upgrading facilitated across many buildings rather than to deal with them individually.

Heritage Buildings and Planning processes

A strategy to upgrade a heritage building should be sensitive to the building. While transfer of density is an option under Heritage Revitalisation Agreements (HRA’s), any arrangement concerning upgrading an existing building fully should not arbitrarily impose onerous upgrade requirements without the fire protection engineer assessing whether the schedule of work is reasonable under the Part 11 guidance.

The strategy should be respectful of the building and relatively easy to implement without invasive processes including un-necessary demolition.

Many heritage buildings can be upgraded with little or no impact on the exterior of the building. This begs the question why such buildings could not be fast-tracked through the planning approval processes? Even simple projects are being routinely delayed for extended periods. Obviously occupancy changes, additions have to be assessed for their impact on the community.

On the whole, the heritage planners are sensitive to the practicalities and will process their reviews in a reasonable time. Planning applications should be fast-tracked where existing construction is involved. By rolling renovations into the mainstream planning process, routine building projects are being held up by complex new- builds which require extended planning processes to obtain public approval. This un-necessarily delays projects in major centres involving conversion to residential and other occupancies. Such refurbishment projects typically have a positive impact on the areas in which they are located; even major conversions and additions- within reasonable bounds- should be encouraged and fast-tracked rather than be excessively scrutinised. If a building already exists it should be implied that it is already appropriate in its location and thereby easily adapted to suit new needs.

In particular consideration should be given to a new process exclusively for existing buildings to facilitate adapted re-use and fast-tracked changed to bring housing supply back into balance.

USING OPTION 2 – THE RISK-BASED APPROACH

This approach enables the proponent to:

Maximize the use of existing heritage features and building features rather than to drive excessive internal changes with greater impact.

Develop a fire strategy around the essential heritage features and compensate for inadequate fire resistance of fire separations and other features by compensating in other ways.

There are several important steps to be followed to achieve this:

A complete fire risk assessment and identification of all potential building code issues should be undertaken before the architectural scheme becomes well established and irreversible. It is not uncommon for architects and developers to make assumptions about the level of upgrading and this combined with a more aggressive scheme of conversion can, in combination with other factors, render the scheme so costly to implement that only key features such as the external walls can be saved. This should be regarded as failure of the whole process.

The impact of the changes that are planned have to be assessed and a rational concept for upgrading the building developed for alignment with Part 11. Based on previous projects the following factors can be considered in bringing the upgrading concept together.

If the fire risk of the building is fully addressed then all the other issues are put in perspective and can be carried forward to the City as part of the process. This builds trust with the authority and also help to put the strategy into better perspective

Assess how the Owner’s aspirations fit into this process. If there is extensive cosmetic work such as renovations of a hotel then those items should be separated from associated upgrade work that will be undertaken. The work usually presents the opportunity to undertake other upgrading work such as those to fire and life safety systems.

The mechanism for the level of upgrading should be clear. However, there may be a compelling argument to take a different approach. This inevitably arises because the features are different than those anticipated. It is a good general principle that the building will tell you what it wants to do and the rest should be how to retain these building features as a fundamental part of an upgrading scheme. If your process works the other way around then you will not be undertaking the project in the best way for the building and you will find yourself dictating to the building fabric rather than the other way around.

Involving a fire protection engineer early in the process is essential as the strategy for upgrading can be discussed before the level of upgrading becomes locked in stone.

STRUCTURAL UPGRADING

Figure 4: External brace on Railway Street: a unique solution to lateral restraint – John Bryson and Partners

The fire protection engineer/code consultant should be able to deliver a broad-based agreement with the authority. This should include the level of seismic upgrading and other upgrading work such building envelope and accessibility.

Without a close working relationship with the structural engineer, the Owner and the fire protection engineer/code consultant, it may be assumed that full seismic upgrading is required. By driving this process the fire protection engineer can determine the actual level of seismic upgrading required achieving significant cost savings in the process.

Some structural engineers are more comfortable working with renovations and have shown flexibility and creativity in their work as well as willingness to align their design to the agreed upgrade scheme. If any engineer or architect tells you that full upgrading is inevitable this is a red flag.

Once the fire protection engineer/code consultant has fine-tuned the fire strategy then the structural engineer should support his or her role and represent the joint position of the team in a meeting with the City.

Figure 5: This feature stair was recently removed as new stairs were created as part of the architectural design.

THE BUILDING PERMIT PROCESS

If the scheme involves architectural changes of significance then there will be an architect retained to carry out a design. Some architects have evolved their service over the years into a full service for renovations. Such professionals are also cognisant of the conservation issues. This is true in both Canada and the UK.

Where there is a major addition to a building such as a horizontal addition to a school or hospital there may need to be a programme for upgrading the building as a whole. This then poses the problem: who should coordinate the project to implement the upgrading requirements? Where the code consultant does not undertake design work, the project typically requires mechanical, electrical and other consultants to complete the design. If a structural engineer or geotechnical engineer is required this makes the task of coordinating the design challenging.

Depending upon the scheme it may be possible to streamline the number of consultants required to complete a project.

Certain fire protection engineering firms undertake design of projects and this enables them to reduce the number of consultants required to implement the design. Much design work in the City of Vancouver until 2001 was carried out on this basis. The same strategy has been used on major heritage upgrading projects undertaken by the Province of BC.

In all cases, it is essential that the agreement on the extent of upgrading be reached before the design development takes place. If not, then it is typically too late to control the extent of work of the consultants and costs get out of control.

CERTIFIED PROFESSIONAL PROGRAMME

Figure 6: This infill Building in Gastown formed part of a block-wide seismic strategy

The predominance of Certified Professionals has enabled them to coordinate the Code conformance of projects. The lack of a streamlined process for carrying out the design of renovations has driven up the number of consultants and the schemes towards full code compliance with relatively few exceptions. This is because the underlying model for conformance is the building code for new buildings which is never an effective fit for heritage and other existing buildings. Unwittingly the CP process, though effective on new buildings, may have complicated and increased the cost of renovation. This along with other factors has reduced retention of features of existing buildings and increased demolition and costs.

If a strategy is worked out by a fire protection engineer/code consultant that is bespoke then it makes sense that the coordination should be managed by the same party and if possible key elements of the design such as the fire protection systems and related work undertaken by the same party.

If the fire protection engineer/code consultant works with the City then certain aspects such as reasonable changes to existing stairs can be worked through with the City building inspector to achieve practical improvements rather than application of literal requirements of the code necessitating replacement of stairs.

Figure 7: Images in a Gastown shop window

SUMMARY

A risk-based approach by which heritage and other existing buildings are fully assessed is typically more flexible and enables retention and heritage conservation to form an integral part of the strategy. Retention of individual building features should drive the upgrading scheme.

Figure 7: Images in a Gastown shop window

An overly adventurous or invasive design scheme for the building will exacerbate the fire and building code problems, escalate construction costs and complicate and delay planning approvals.

A streamlined approach to planning is required where there are nominal exterior changes and uses are consistent with the area plan. This would help facilitate residential conversion and make rental and other housing more affordable.

Fire and building consultants should be responsible for reaching consensus with the authority; they should lead on issues such as the reuse of existing stairs and exposed heavy timber. Strategies should be adapted to retain key heritage features.

Some details are best left to the District Building inspector to work out on site. Such issues should be identified at the agreement stage. This can avoid the need for costly Alternative Solutions.

A new process for renovations should recognise the bespoke nature of upgrading and use a customised checklist based on the agreement with the authority rather than a complex checklist based on new building projects.

A reduction in soft costs can be achieved if the fire and building code consultant can carry out much of the design work rather than reliance on a conventional team less familiar with fire and life safety systems.

Structural consultants should rely on the upgrading strategy reached with the City as significant reductions in costs can be achieved if aligned with the nature and extent of changes. The fire protection engineer/building code consultant should take the lead on this.

Prepared By: John T. Ivison

January 15, 2016

Design and Construction of Firewalls

Date: Bulletin No. 2- January 5, 2017

Subject: Design and Construction of Firewalls

Issue Number: 2017-01

Figure 1: Typical masonry wall in wood frame construction.

Introduction

Recent developments in firewall construction demand some re-examination of the original purpose and functions of fire walls.

Firewalls are, essentially, a tool for reducing the potential for fire to spread uncontrollably across a property. The original concept of ‘fire divisions’ was that fire would not spread out of the fire division under the worst conditions with no attempts to extinguish it.

To achieve that end, the property would either separate buildings by sufficient spatial separation or subdivide buildings by firewalls such that the fire would be restricted to the fire division. Although the term building area is now used for this purpose, the principle is the same. The National Building Code of Canada (NBCC) defines a firewall as a fire separation that subdivides or separates adjoining buildings; such fire separations restrict fire to a prescribed degree and most importantly, have structural stability under fire conditions.

It is important to differentiate conventional fire separations from firewalls. A fire separation functions as a barrier to protect against fire spread but is easily pulled down in event of collapse of the structure on either side of it. Such fire separations are also not continuous as firewalls typically have to be. You can rationalise this by regarding a fire separation as a shield against radiation and fire penetration. Other occupancies and occupants are protected against the immediate effects of fire but typically there will either be, for example, evacuation or intervention by the fire service before collapse occurs. In the case of firewalls, they will either stay in place or function to prevent total collapse and ultimately fire spread into the next building with no intervention by the fire service or others.

In the NBCC, firewalls are typically 2 hour rated for occupancies equated with a lower risk and 4 hour rated for Group E (retail), F1 (high hazard industrial) and F2 (medium hazard industrial) occupancies. This does not preclude higher ratings for unusual high risk situations. Maximum Foreseeable Loss (MFL) firewalls- used by Factory Mutual and other large insurers- may be more onerous and generally apply to unusual structures such as large- scale industrial operations.

In certain cases, horizontal offsets in a firewall may be required, which require special design consideration to ensure structural stability of offset firewalls in particular.

To prevent fire spread around a firewall, firewalls in conventional combustible or non-combustible buildings generally require parapets (vertical extensions through the roof). The exception is where the roof is of reinforced concrete construction and has a fire resistance of at least one hour for a two hour firewall or two hours for a four hour firewall. This is somewhat of a relaxation over traditional firewall construction as in theory, the roof could collapse in over an hour leading to collapse of the firewall. The assumption is that the reinforced concrete construction should be less subject to collapse, damage and flame penetration due to its homogeneity.

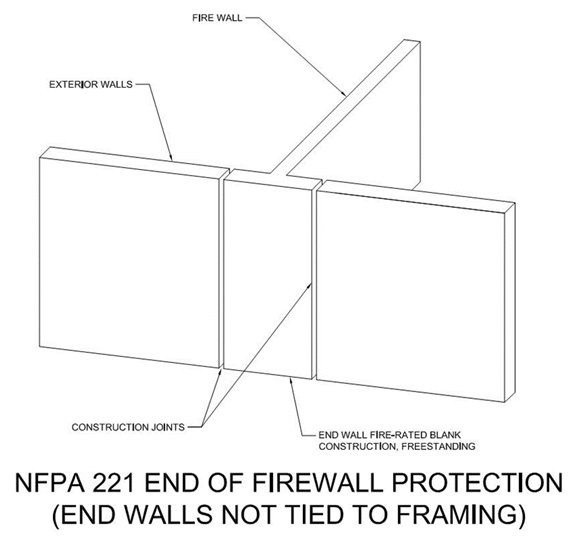

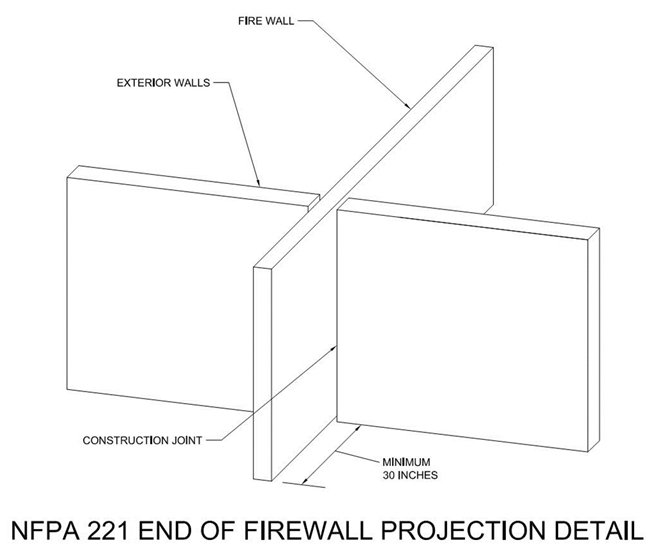

Although the Code does not permit combustible material to extend around a firewall at the ends, it does not require the provision of extensions which have been traditionally used to prevent involvement and ‘burn around’ of the firewall at combustible walls. Traditional details by way of tees or extensions of firewalls through combustible walls are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Tee- section at end of firewall acts as fire-break.

Figure 3 Projection through end of firewall to prevent fire spread around the wall.

The NBCC requires that a firewall supporting structure that is supported on a firewall or connected to a firewall have the same fire resistance as the firewall so that structural failure of those supporting or connected members does not result in the collapse of the firewall.

The exception is where the firewall consists of two back to back firewalls each tied to its respective building frame and designed so that collapse of one firewall will not cause collapse of the other. This is a typical arrangement of firewalls as each side of the firewall can be tied to the supporting structure in the normal fashion. Also, where an exterior wall has a fire resistance an addition can be made by having new independent wall on the new building of similar construction provided requirements for openings in the wall and parapets are met.

Figure 4 Back to back firewall construction. Note that the only connection is at the roof flashing.

It should be noted that the NBCC permits each firewall in this situation to have half the required rating of a free-standing firewall. This is a compromise as the idea is that with a collapse on one side of a building the fire spread will not occur across the boundary with no attempts to extinguish it. It is unlikely with a total burn-out that a one hour wall will be able to survive once the first wall collapses. Where back to back walls are provided, the original intent recognised that collapse on one side – with unprotected steel structure for instance – could occur within 10 minutes. In this circumstance, it seems unrealistic to expect half the required rating to be sufficient to meet the worse case criteria. The same relaxation is not permitted in the US.

Since the 2005 NBCC, materials other than masonry or concrete have been permitted provided the assembly is protected against damage that would compromise the integrity of the firewall and provided the design of the wall complies with 4.1.4.17 of the NBCC.

The Appendix A to Part 3 claims that the damage references damage occasioned in normal use. This is incorrect.

The traditional use of concrete and masonry was to enable the firewall to resist the effects of collapsing elements some of which could become displaced by the collapsing forces. The debris pattern following collapse of a structure suggests that this is a realistic concern. The suggestion that this is a wear and tear issue may have arisen as a result of other concerns. In other occupancies, damage to firewalls is as a result of damage by vehicles – particularly those used for loading in warehouse and retail occupancies. However, the nature of this damage such as that experienced in carpet storage warehouses suggests that construction other than masonry or concrete would be even more susceptible to damage.

Although most collapses exhibit a debris field in the footprint of the building, in the worst cases, debris has been discharged and deposited considerable distances from buildings. In progressive collapses, such as in the World Trade Centre, debris was displaced to 600 feet from the perimeter of the building. The suggestion is that the debris projection may increase with building height and the mechanism of collapse.

For this reason, it is reasonable to provide structural and fire resistance to direct/localized impact from collapsing members and falling construction debris or other objects during a fire event.

Figure 5 Debris field in wood frame construction

The reference to Part 4, Structural Design, references specific requirements to ensure the structural stability of firewalls. Firewalls are designed to resist the lateral design loads set out in Part 4 or a lateral design load of 0.5kPa under fire conditions. In Imperial units, this force on a conventional 100 foot section of wall 16 feet high translates to a lateral force of 16,700 pounds.

Typically, firewalls are not designed for explosive pressures although this is stated as an objective in the NBCC. Where an explosion hazard exists other standards such as NFPA 68 for explosion venting may be utilised to vent the explosion and relieve pressures before they rise above the maximum tolerable pressures of firewalls.

An important consideration in the design of firewalls is thermal expansion as well as allowance for movement due to seismic and other forces. For further information on both thermal movement and structural deformation refer to the CCMPA paper on firewalls by Gary Sturgeon.

Firewalls are of different types:

The double firewall previously described.

Cantilever type

Tied type

Weak-link firewall

Figure 6: Typical double firewall- Credit ASCE Knowledge and Learning. Note the clearance between firewalls for thermal expansion, resistance to pounding under seismic forces.

The cantilever firewall is essentially self-supporting with the only connection being at the foundation. As this system is dependant on vertical reinforcement the height limit is around 10 metres. As the wall is free-standing the roof is independently supported on each side. Clearance up to 150mm is required for thermal expansion and movement depending on height and length of bays.

Figure 7 Cantilever firewall.

In tied firewalls, lateral stability is dependent on the building frame. The firewall may contain a single or double column. The pull of collapsing steel is resisted on the non-fire side.

Figure 8 Tied firewall with double column or single column encased in masonry/concrete construction.

Figure 8 Tied firewall with double column or single column encased in masonry/concrete construction.

By using weak link tied firewalls, structural components are supported by the firewall in such a way that the failing structure may collapse without damaging the integrity of the firewall. Weak link connections are used with tied firewalls where the wall is braced with wood construction. Where the wood joists run perpendicular to the wall, the joists can be fire cut to enable them to collapse away from the wall under fire conditions. This is common in traditional heavy timber construction. Further details are available in the CCMPA paper referenced above.

Summary

Firewalls are designed to prevent fire spread under worst condition with no attempts to extinguish the fire.

Traditional firewalls have been constructed of masonry/concrete.

The use of alternative materials – other than masonry or concrete – has been permitted since 2005 and will be addressed in our next bulletin.

Structural stability is a key consideration and can be addressed in different ways by different types of firewall.

Walls are typically continuous and will have a 2-4 hour rating depending on the occupancy.

Traditional firewall construction had good damage resistance to prevent against penetration of the wall by collapsing structure.

Horizontal and vertical movement in walls arises from thermal and other effects- clearances are required to permit movement and prevent damage to firewalls.

Parapet and end- wall details are important to prevent fire spread in certain types of construction.

Proven performance since the Great Fire of London: 1666

Figure 9: Painting of the Great Fire of London.

Prepared By: John T. Ivison

January 5, 2017

Water Supplies for Fire Fighting

Figure 1: Typical fire pump arrangement taking suction from reservoirs.

Introduction:

Much confusion exists as to what is an acceptable water supply for firefighting. Historically, water supply was tied to the ‘fire risk’.

Fire risk can be defined as the product of the frequency of a fire and the consequences resulting therefrom. This requires integration over the range of possible fires and the resulting impacts.

The fire risk may often be confined to a single building. However, on the municipal scale of risks, all other risks such as transportation, outside storage and electrical/gas distribution stations need to be taken into account in assessing the need for water and logistical resources to fight fires/facilitate rescue. Although these are not specifically included in the fire flow calculations it does illustrate why the municipal demand has to account for risks on a larger scale than the typical building. Consequently, the definition of a water supply in these situations is typically not confined to a building but rather reflects the ‘risk spectrum’ in the municipality.

Figure 2: Risks – such as this exhibition – fall outside the definition of a building.

The difference and scale of fire fighting on the municipal scale has led to the myth that methods of determining fire fighting water supplies are overly conservative in comparison to individual building needs. In fact, the reality is that while the focus of those who design buildings has to be on the building they are considering, we cannot design water supply infrastructure based on the assumption that fire will not spread beyond the building. In fact, the performance over a municipality reflects the inventory of existing buildings and not just the new structures brought on stream over time.

Risk at the municipal level is influenced by the prevailing risk culture. It is generally recognized that up to 95% of risks are behaviourally influenced. Whereas the building code sets out risk as an occupancy and construction issue the uncertainty at the municipal level whether we like it or not has led to a conservative approach to expected response to fires largely based on experience and feedback from real fires. As uncertainty arises largely as an outcome of human failures there is a limit to prevention and limits through effective design.

Also as you can see from Figure 3, the actual fire risk may increase as buildings age. Building risk may increase as a result of additions and other changes which may challenge assumptions made at the time the building was new. As the majority of buildings are existing the fire flow for new buildings may be significantly less than the block risk that arises from a mix of relatively new and older structures.

For this reason, both in the US and Canada, there are recognised municipal standards that have been developed to enable a robust infrastructure to be designed to respond to the scale of fires anticipated. The general approach used varies in terms of the scale and character of the place as well as the emergency response organisation. Traditionally the level of public fire protection is graded on a scale (in Canada 1-10) and this is typically reviewed and revised as the risk changes over time.

This means that fire risk for a single building or complex is one thing, municipal risk is something entirely different. Also, the larger fires taken on a macro basis need only meet a residual water pressure of around 138 Kpa (20 psig) reflecting the fact that flows are normally boosted by fire apparatus.

Figure 3: Typical block risk diagram used to develop municipal risk profile: Courtesy Fire Underwriters’ Survey

Experience with assessing fire risk is essential if the assessment of water supply needs is to be realistic.

Figure 4: Remote recreational facility

Typical scenarios where specialist assessments are often undertaken to determine fire flow and design water supplies include:

Townsites requiring improvements in the water supplies for fire protection (for instance historic towns, logging/construction camps).

Expansion of town or city supplies into new subdivisions/infill development- often for housing (sometimes with limited capacity or dead-end mains).

Water supplies for larger scale industrial sites and unusual structures.

Figure 5: Expansion of this subdivision in West Vancouver in the 1980s was sprinklered (to NFPA 13D)

Figure 6: Listed pier structure with poor fire service access

All of the above require an holistic assessment of the fire potential. In cases where all the buildings are protected by automatic sprinklers other factors come into play. Most standards of public protection take account of reductions in the fire flow arising from sprinkler protection afforded to the buildings. In the municipal context, relaxations in the extent of protection (such as NFPA 13R) provided as economic incentives to encourage the use of sprinklers need to be taken into consideration.

Figure 7: Fully involved fire in a building under construction.

In the case of suburban areas, the use of sprinklers has been used to mitigate risk in cases where fire response is extended due to urban sprawl. In these cases, relaxations in both building code provisions as well as access and hydrant spacing have been utilised. Typically, smaller mains might be permitted as the result of lower fire flows. These flows however, are still significant relative to sprinkler demand and sprinkler pipe sizing.

Where increasing density utilises 4-6 storey wood frame construction fire flows may rise, and risk in construction may need to be addressed. Historically however, this risk has been accepted based on the benefits of wood frame in terms of cost effective residential construction. The scale of recent 4-6 storey construction projects have brought this somewhat into question.

Where anomalies occur in an area that is predominantly of lower fire risk it is often the practice to mitigate the risk by protecting the property to a higher standard. These are regarded as risk anomalies. For instance, this may occur in areas where supermarkets and other risks have been introduced into largely residential areas. For these situations, the FUS or ISO requirements are not typically fully applied unless other factors are at play.

In the case of industrial sites, more reliability is typically required due to the industrial processes and insurer requirements based on the exposure to loss. Design of water supplies in these situations would involve at least two supplies and often tertiary and quaternary supplies.

Figure 8: Water supplies in this instance were split to improve reliability and facilitate maintenance

Analysis of these situations is beyond the scope of this paper but more information can be obtained by calling our office. In these situations, more reliability is required than mandated by the National Building Code of Canada (NBCC).

Some provisions of the current code go against historic principles that correlated reliability requirements with fire risk. For instance, there is no credit under any FUS or ISO standard arising from the use of standpipe and hose systems. This is in part as a result of the fact that fire flow standards reflect the reactive nature of fire service operations and often the lack of internal fire suppression.

Now that we have provided this overview we should now look at what is mandated under the NBCC.

NBCC requirements:

3.2.5.7 of the NBCC requires an adequate water supply for every building. Sentence 3.2.5.7(1) references Appendix A which attempts to clarify what is meant by an adequate water supply. The reference under previous editions of the NBCC to the Fire Underwriters’ Survey has been removed and the US standard only is referenced- as a useful document- in the Appendix.

Sentence (2) relaxes this situation for buildings sprinklered in accordance with 3.2.5.12 or buildings with a standpipe system complying with 3.2.5.7 (1). The FUS and ISO standards address risk arising from individual sprinklered buildings, exposures and other factors most importantly construction, area, occupancy as well as the number of storeys. The order of magnitude of fire flows using these methods significantly exceed the water supply needs of sprinkler systems. As such they again reflect the magnitude of risk in the context of failure to control the fire.

In the case of sprinklered buildings, risk is not entirely eliminated- there is a finite probability of failure- and external risks and other factors can intervene to create fires that go beyond the scale of internal fires. No credit is typically provided for a standpipe system as such systems are reactive and it may be difficult to quantify the difference between the use of hydrants and standpipes on the fire.

Figure 9: Sprinkler system manifold for a large facility.

Appendix A of the NBCC references many natural and man-made sources of water. If natural sources feed automatic sprinkler systems and private hydrants, special consideration is required to ensure that fish are protected and that other matter from the natural sources (weeds and algae for instance) do not enter the system, blocking nozzles or fire apparatus.

Reference standards such as NFPA 20 for fire pumps discuss strainers and suction arrangements to minimise this risk. Salt water pumping systems such as those used on piers and wharves or coastal mills are subject to corrosion and contamination from fish, vegetation as well as silting which can wear out pump seals. Consequently, the design of such systems is often focussed on minimising emergency starting of these pumps in preference to pumps using other- such as potable- supplies.

A similar problem can be experience with reservoirs, suction tanks and ponds which become subject to growth and nurturing of aquatic species. This is reduced if the systems are designed to prevent stagnant water by turn over of the contents. This is relatively easy to achieve with tanks and reservoirs. In the case of rivers and other natural sources special consideration is required. Automatic flushing of the suction arrangement by back-flushing with water can prevent ingress of fish and other matter.

Figure 10: Fire Service training using ground monitor

The starting sequence of multiple supplies using pumps is important to ensure inadvertent starting of pumps. In particular where a combination of municipal supplies with private supplies is available, it is typical to run the mains (looped or tree formation) on potable water to minimise potential contamination by other supplies from private or natural sources. To prevent inadvertent starting of pumps the mains are usually kept at an artificially high pressure- through jockey or service pumps- so that, when sprinklers discharge, there is a rapid drop in pressure to enable pumps starting at a pressure reasonably below the maintained pressure on the system.

The reliability of size of water supplies becomes a concern where factors affect the fire risk. For instance, if there is no fire department then additional capacity is advisable depending on the capability of any on-site resources. Also, the choice of private self-draining standpipes over hydrants may be suitable if the fire department has limited capability/training with large hoses.

Figure 11: Lack of sprinklers in one area led to this conflagration/total loss of a fully sprinklered building.

In situations with multiple supplies, fire flow is less of a concern as dependence may be as much on private supplies as on the municipal supplies. It is noted that if a supply from the authority or private water supplier needs to be boosted then it is generally regarded as a ‘poor’ water supply although adequate for certain situations where the risk magnitude is acceptable. This usually relies on some capability of the supply to meet sprinkler demand alone without hose demand included.

Figure 12: Booster pump (electric drive)

The NBCC Appendix A indicates that consideration should be given to ensure that water sources are accessible to fire department equipment. This is typically only necessary where fire departments take suction from these supplies as their source of water. This is typically not required when fire protection is automatic from private sources and the supply forms part of an integrated fire protection/fire fighting strategy.

However, where combination supplies are utilised it is important to consider the role of the fire service, compatibility of private equipment (such as hydrants) with fire department appliances and equipment. For certain structures, fire service access may be limited to such an extent (for instance on piers served by railways with no roadways per se) that the fire strategy must compensate in terms of system design and reliability.